It's 2500 B.C. in southern Italy and we are Greek settlers busily trying to develop Magna Grecia - the cradle of civilization as the game's subtitle puts it. In front of us lies a map of the area with a number of already established small settlements and our task is it to develop these villages to flourishing cities: cities with markets and roads to other cities.

The more road connections a city has to other cities the more trade its markets will generate and hence the more valuable the markets are at the end of the game. However, only active markets can generate points. To become active, a market must be either in a player's own city or in a city which has a direct road to one of that player's cities. Besides markets cities themselves can generate points at the end of the game if they connect to any of the randomly placed oracles on the map.

Player sequence is determined by twelve cards, each representing a complete round of the game. Each card show the players' turn sequence and the actions which may be performed by the players in that round. The principle actions are a) to place road tiles, b) to establish or expand cities by placing city tiles and c) to re-supply tiles from stock. Each card shows how many tiles of a kind a player may place or take.

The card system is fair and only "semi random": all players are three times each first, second, third or fourth player in a round and the quantity of tiles available is one each of high, medium and low. The cards are arranged in three sets of four with each player receiving each turn sequence once per set. The cards are placed face up and the card for the current round is handed to the players in sequence. This provides some limited possibility for planning ahead as both the quantity of tiles and the players' sequence of the next rounds are visible, too.

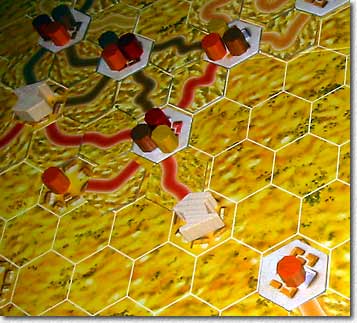

Development of Magna Grecia starts at the edge of the board and the road and city system develops towards the center of the map. It is obvious that cities located in the center of the map will most likely end up with a lot more connections to other cities than those at the edge of the map. That's why players will quickly try to build roads towards the center and at the same time they will start to place markets in villages at the center of the map hoping that these villages will be come proliferating cities towards the end of the game.

This sounds easier than it is because in order to

become an active (i.e. point generating) market it must be in the immediate vicinity

of one's own city. And in order to establish a city anywhere on the map one must

build a road to the corresponding village. By mid-game the center of the board

usually becomes rather crowed and building the required road system to interconnect

the desired cities becomes increasingly difficult. The more so as there is ample

possibility of roads being cut off by other players.

This sounds easier than it is because in order to

become an active (i.e. point generating) market it must be in the immediate vicinity

of one's own city. And in order to establish a city anywhere on the map one must

build a road to the corresponding village. By mid-game the center of the board

usually becomes rather crowed and building the required road system to interconnect

the desired cities becomes increasingly difficult. The more so as there is ample

possibility of roads being cut off by other players.

While road building is free players must pay points for establishing or expanding cities as well as for placing markets on villages or "foreign" cities. This makes it necessary that players "cash in" some of their markets already in mid-game by deactivating them (turning them sideways). This immediately generated the market's value in points for the player. Of course players will try to make sure that they only cash in those markets that are in cities which will not increase their number of road connections.

Careful consideration is required here as not only may a possible growth in connections be overlooked but also does this allow other players to build markets in that city at a lower price (the price to be paid for placing a market depends on the city size and the number of markets active in a city).

"Magna Grecia" requires tough strategic and tactical decisions by its players and is hardly influenced by random "luck factor". Starting with the decision to either go for a "market focused" or an "oracle focused" strategy up to the decisions about which markets to establish and how to develop one's road system makes the game very challenging.

Interestingly, the final score in our game was very close for the top three scorers (within 5 points) and all scores were in the 40's and lower 50's on a "Kramer track" which ends at 49! My interpretation is that we did not play offensive enough to exploit the full scope of the game's possibilities. Only in retrospect did I discover the true depth of the game.

All of this suggests that "Magna Grecia" is one of the highlights of this year's games. And in fact our score for the game suggest this, too. However, there was one low score of 5 (out of 10) and it is mine, the reason of which I want to briefly describe:

Playing "Magna Grecia" involves a lot of counting (road connections, markets, city tiles, and distances) in order to determine one's "best possible move". While I find this acceptable in a two player game I dislike this in multi-player games, since it tends to create a lot of idle time for the non-active players. It took us 150 minutes to play the twelve rounds - this is 12 minutes per round or 9 minutes of idle time for each player per round. However I must admit that we played the game not quite to the rules as we accidentally did not place the turn cards face up and therefore it was not possible for us to precisely plan ahead for the next round. This would have provided the idle players with some food for thought but might also have increased the average turn duration of the active player as this additional bit of information must be taken into account as well when executing one's turn.

| View/add comments here |

Westpark Gamers score: 7.0

Aaron Haag

01-05-2003

This relatively recent offering has not created a lot of buzz, which seems understandable as it is basically a very abstract "builder" game. But it has some interesting twists, which make it worth a second look. And the game material is fun - huge plastic blocks that wake the child in us.

Forget the Native-American theme (which is a nice flavour, but not in any way necessary for the game)- this plays like a kind of 3D-boardgame-Tetris (remember the good ol'days?).

A square board is divided into 4 smaller squares, surrounded by a track for the "shaman", who is in fact a fancily named scoring pawn. Another board is purely for scoring (slightly confusing, as it uses wild colors, and the direction of the track is inside out. Actually it happens easily that you move the pawn in the wrong direction, and not all the spaces are numbered, so you might not realize your mistake!).

Each player owns 4 ½ double blocks of "3D-Tetris blocks" (more with less than 4 players), one in her/his own color, another in a "neutral" color. Together these two build a "pair" which form a perfect cube, and you can only "open" a new block after you have finished the old one. This means that you have to take turns playing your own and the neutral color.

The blocks themselves are all the same, each the exact half of a cube. They can be placed on the ground of the board, or atop each other. But no "Villa Paletti" or "Bausack" shenanigans here, this isn't a dexterity game! Each placed piece has to rest completely on 3 sides, so there can never be any "overhanging" parts. This limits the choice of playable spaces somewhat, a variety of forms could have made the game more interesting, but also even more intense. Even in this simple form one can spend quite a while thinking about the best placement.

The basic idea of the game is this: Each player first plays a piece, THEN moves the shaman 1-4 spaces. The shaman always looks down the row where he is placed after movement, towards the middle of the board. Each color he sees is NEGATIVE for the player, the higher it is when seen the worse. Seeing a first level color gives 1 negative point, 2nd level 2, etc.. As the game follows the three dimensional laws of obstruction the shaman can only see one color per level, the others will be obstructed.

When the shaman ends his move on the exact corner space of the surrounding

track, he looks at the "pueblo" from ABOVE, but only at one of the 4

corresponding squares. Now each color space gives 1 negative point for the respective

player.

When the shaman ends his move on the exact corner space of the surrounding

track, he looks at the "pueblo" from ABOVE, but only at one of the 4

corresponding squares. Now each color space gives 1 negative point for the respective

player.

And that's it -after all players have played all their pieces, the shaman makes his final (and most deadly) round - now EACH square of the surrounding track is counted (takes quite a while), so the final position of the pieces is of utmost importance.

It is obvious that this is an advanced game of hide and seek: You want to play your color pieces in a way which makes them "invisible" by hiding them behind other or neutral pieces - more difficult than it sounds!

Also the present position of the shaman has to be taken into account - If you place a prominent colored piece close to the future spaces of the shaman's movement, you can bet your tipi on the fact that other players will make use of this and give you lots of negative points.

The problem is that this can not always be avoided….

This is the basic game, easy, but challenging enough. We were of course foolish enough to try the "professional" version, which brings two new rules to the game.

First: now there are "holy" spaces, designated by 1-4 counters, which can never be used for building upon. This limits the building option severely, and makes for a high rise pueblo with noticeably higher negative scores, as there are fewer possibilities to hide.

Second: Two times in the game, there is bidding (with negative points) for the turn order, highest bidder selects first. Usually you want to go earlier, so your pieces have a better chance of being built upon and thus being hidden later on.

I personally like the second option with the bidding, the first option simply heightens the hidden luck element in the game - the movement of the shaman! With the limited building option you will be forced to take risks with your building, if the other players now conspire against you (and they often will!), you will lose many more points than in the basic version. Also, the reduced space actually limits your playing possibilities severely, so having more options in the basic game is actually the TRUE professional version. Strange that the game designer didn't reflect on that…The corner spaces are also now totally unimportant, as this kind of scoring will now be much less effective in comparison to the high-rise scoring.

But our opinions differ on that, Walter preferred the "advanced" version, but than he hasn't played the basic version. I would certainly only play without holy spaces but with turn bidding if I ever replay this game.

All in all this is a very decent offering - The game is abstract without being dry, the building element is fun, and the game is easily explained without lacking tactical depth. It would also certainly appeal to non-gamers, and family gamers.

I could have imagined a more interesting game with different building parts, but that might have been a cost decision - more forms for the plastic pieces would have cost more. Also the game might get old more quickly than other games with replays, I'm pretty sure that there is only "one right way" to play, and once you have found that, it becomes repetitive.

| View/add comments here |

Westpark Gamers score: 6.75

Moritz Eggert

30-4-2003