Moritz packte mal wieder eine Neuerwerbung aus, und mit der ihn auszeichnenden Genialität

ging er daran, uns die englischen Spielregeln aus dem Stegreif heraus in verständliches

Deutsch zu übersetzen. Bei den üblichen WPG-Rückfragen zu Regel-Details musste er leider

immer passen, da er sich erst selbst durch die Beschreibungen hindurchkämpfen musste, und

die Antworten selbst noch gar nicht kannte. Nach 20 Minuten waren wir durch die vier

Druckseiten Regelwerk hindurchgekommen und hatten eine vage Vorstellung davon, was uns

jetzt erwartete.

Moritz packte mal wieder eine Neuerwerbung aus, und mit der ihn auszeichnenden Genialität

ging er daran, uns die englischen Spielregeln aus dem Stegreif heraus in verständliches

Deutsch zu übersetzen. Bei den üblichen WPG-Rückfragen zu Regel-Details musste er leider

immer passen, da er sich erst selbst durch die Beschreibungen hindurchkämpfen musste, und

die Antworten selbst noch gar nicht kannte. Nach 20 Minuten waren wir durch die vier

Druckseiten Regelwerk hindurchgekommen und hatten eine vage Vorstellung davon, was uns

jetzt erwartete.

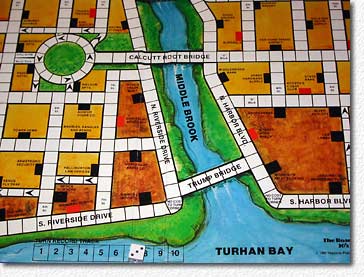

In einer amerikanischen Großstadtszenerie (aus welchem Jahrzehnt auch immer) wird die ungebrochene Dominanz der Verbrechersyndikate nachgespielt: alle Mitspieler sind Gangster; jeder muss seine Beute, ausgedrückt als Geldsumme, vom Ort seines Verbrechens bis zu seinem Unterschlupf transportieren. Jeder zieht zufällig eine Karte, auf dem die Lage seines Unterschlupfes vorgegeben ist. Das ist der Zielort. Jeder zieht zufällig drei weitere Karten, auf denen die möglichen Positionen seines Verbrechens eingetragen sind. Eine davon darf er als Startposition für seinen Auftrag auswählen. Natürlich sollte er diejenige auswählen, die am günstigsten zu seinem Ziel liegt. Für den Transport der Beute bekommt jeder ein Fahrzeug, mit dem er sich für alle sichtbar auf den Straßen des Stadtplans vorwärts bewegt. Maximal zehn Felder pro Zug.

Reihum abwechselnd spielt jeweils einer der Mitspieler den Polizeikommissar und ist damit Chef über eine Flotte von zehn Polizeieinsatzfahrzeugen, mit denen er die Gangster am Einfahren der Beute hindern soll. Jedes Polizeifahrzeug darf sich pro Zug um acht Felder bewegen. Die Gangster bekommen also in bezug auf die Reichweite ihrer Fahrzeuge einen kleinen Vorteil, dafür liegt der Vorteil in bezug auf Masse klar auf Seiten der Polizei.

Allerdings ist ein einzelnes Polizeifahrzeug

noch kein Hindernis für einen Kriminellen, er kann ohne jegliche Einschränkung daran

vorbeifahren. Erst zwei Polizeiautos, auf einem einzigen Feld übereinander

gestapelt, bilden eine Sperre, die nicht passiert werden darf. Um einen Gangster

aber ganz unschädlich zu machen, bedarf es schon vier Polizeifahrzeuge, die bis in

unmittelbare Nähe des Betroffenen vorrücken müssen. Da tut sich ein Gesetzeshüter

schon schwer, alle Verbrecher zur Strecke zu bringen. Kurz gesagt, durchschnittlich

drei Viertel der Kriminellen können ihre Beute ungehindert nach Hause bringen.

Allerdings ist ein einzelnes Polizeifahrzeug

noch kein Hindernis für einen Kriminellen, er kann ohne jegliche Einschränkung daran

vorbeifahren. Erst zwei Polizeiautos, auf einem einzigen Feld übereinander

gestapelt, bilden eine Sperre, die nicht passiert werden darf. Um einen Gangster

aber ganz unschädlich zu machen, bedarf es schon vier Polizeifahrzeuge, die bis in

unmittelbare Nähe des Betroffenen vorrücken müssen. Da tut sich ein Gesetzeshüter

schon schwer, alle Verbrecher zur Strecke zu bringen. Kurz gesagt, durchschnittlich

drei Viertel der Kriminellen können ihre Beute ungehindert nach Hause bringen.

Wen es aber erwischen soll, das hängt zum einen von der Ausgangslage ab, die war ja mehr oder weniger zufällig über das Stadtgebiet plaziert ist, zum anderen aber auch von den persönlichen Beziehungen zur Polizei: diese ist nämlich bestechlich. Vor jeder Runde kann jeder Gangster einen Betrag spendieren, mit dem er sich das Wohlwollen des Gendarmen erkaufen kann. Damit kann sich der Wachtmeister darüber hinwegtrösten, dass er in dieser Runde mittels Verbrechen keinen Gewinn erzielen kann. Leben und leben lassen. Eine Garatie für Straffreiheit ist die Bestechung aber nicht. Soweit klingt alles gut und das Spiel scheint vernünftig. Überdurchschnittliche Bewertung.

Jetzt aber kommt der Knackpunkt.

Die Fahrstrecke, die ein jeder Gangster vom Tatort bis zu seinem Unterschlupf zurücklegen muss, ist von der Länge und von der Stadtlage rein zufällig. Wenn man die richtigen Karten gezogen hat, muss man gerade mal drei Felder weiter ziehen und ist nach seinem ersten Zug bereits zuhause. Wenn man Pech hat, muss man quer durch die Stadt fahren, und hat evtl. keine Chance gegen zehn Polizeifahrzeuge. Die Beute, die ein jeder als Siegesprämie einsteckt, ist auch zufällig. Wer Glück hat, bekommt für seine unbehinderte 3-Felder-Fahrt 25.000 Dollar, wer Pech hat, kämpft um den zehnten Teil dieser Summe gegen den gesamten Polizeiapparat in der Innenstadt. Was hat sich der Autor bei diesem Prinzip gedacht?

Damit das ganze aber nicht so offensichtlich unlogisch über die Bühne geht, hat jeder Spieler noch zwei Ereigniskarten, mit denen er das Ergebnis der Beutezüge beeinflussen kann. Z.B. kann er kostenlos aus dem Gefängnis freikommen, falls ihn die Polizei erwischt haben sollte. Dies ist mindestens 1.000 Dollar wert, aber nur, wenn man im Gefängnis gelandet ist. Oder er darf ein Polizeiauto aus dem Weg räumen. Das kann etwas wert sein, wenn einem die Polizei dicht auf den Fersen ist. Für die Mehrheit der erfolgreichen Verbrecher bringt diese Karte aber nichts. Nach einer Super-Karte aber kassiert man am Ende der Runde die Beute eines Mitspielers, die dieser gerade sicher nach Hause gebracht hat. Das kann dann schon 25.000 Dollar wert sein. Und den überraschten Mitspieler kostet es auch nochmal 25.000 Dollar, macht insgesamt 50.000 Dollar Unterschied, oder? Das ist ca. zehn Prozent der insgesamt zur Verfügung stehenden Geldsumme oder die Gesamtausbeute von sieben Runden biederer Kriminalität!

Macht es Sinn, einem mitspielenden Gangster, der sich vielleicht durch ein geschicktes Täuschungsmanöver erfolgreich zu seinem Unterschlupf durchgekämpft hat, die verdiente Beute abnehmen zu dürfen, nur weil man zufällig die richtige Ereigniskarte auf der Hand hat? Und weil der Gegenspieler nicht zufällig eine Karte gezogen hat, mit der er dieses Hijacking abwehren kann? Ist das nicht ziemlich frustrierend für einen von beiden? Meint der Spieleautor wirklich, dass allein unberechenbares Chaos eine gute Spielidee abgibt?

Hier geht es um die prinzipielle Frage, warum wir spielen und welches für jeden Mitspieler der Erwartungshorizont eines Spielabends ist. Ich sehe das unverzichtbar so:

Wenn ich ein kluges Spiel spiele, dann möchte ich für mich Vorteile sehen, wenn ich klüger bin als die anderen. Bei einem Gedächtnisspiel möchte ich aus meinem Gedächtnis Kapital schlagen, bei einem Verhandlungsspiel aus meinem Diplomatiegeschick, bei einem reinen Glücksspiel aus Fortunas Begünstigung und bei einem Kampfspiel aus meiner Kampferfahrung, aus meinem Löwenmut oder aus meiner Fähigkeit zu taktischem Jammern. Wann immer ich mich auf ein Spiel einlasse, möchte ich von vorneherein taxieren können, ob und welche Spielereigenschaften jetzt gefragt sind.

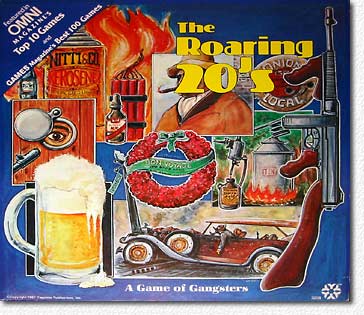

Was bietet diesbezüglich "The Roaring 20's"? Ungerechtigkeit in der Schwierigkeit der gestellten Aufgabe, Unlogik beim jeweilige erzielbaren Erlös, Willkür in der staatlichen Verbrechensbekämpfung, Unberechenbarkeit bei den asynchronen Einflußmöglichkeiten der Mitspieler. Was lernen wir denn aus diesem Spiel? Die Welt ist bösartig und korrupt, Verbrechen zahlen sich in der Regel aus, Planung und Geschick zeitigen keinerlei Früchte und die Polizei ist immer auf der Seite der größeren Dollarbeträge.

Weil wir im Formum der WPG nun mal gerade dieses Thema diskutieren: Dieses Spiel ist in höchstem Grade "politically incorrect". Auch weil der Autor in der begleitenden Beschreibung zur jeweiligen Aufgabenstellung bedenkenlos zu jeglicher Art von Einbruch- und Diebstahls-Deliken vorgibt und zynisch dazu auffordert, dabei das Wachpersonal umzulegen oder die Konkurrenten aufzuhängen.

| View/add comments here |

Die Westpark-Gamers vergaben die mäßige Wertungsnote von 2,5.

Walter Sorger, 25.4.2003

Some tips for winning strategies

Some tips for winning strategies

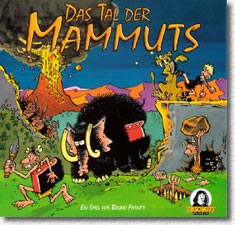

Of course “Tal der Mammuts” is not a clear-cut strategy game. Luck plays a huge factor in being successful in building a huge and prosperous tribe. Many an event card can ruin your best laid plans. But because there are some wargame elements in this game (very light ones, by the way), some tested strategies which work in games of this kind will better your chances in surviving the stone-age battle. And if you are already dependent on luck, why not better your chances by playing well?

1) Choosing your starting space

This might well decide if you win or lose, so it is a decision you should not make lightly. Many factors have to be taken into account. Of course it is preferable to be as far away of other players as possible (but see “my best friend is my neighbour” below), so spaces close to the rim of the board are more interesting than central ones, where everybody will be your enemy. You should always choose a plain hex as a starting space, chances are good it will see a crop if you use the initial planting rule. Later in the game it will be much more difficult to see your crop grow, actually I’ve yet to see a game with many high-yielding crops, it just doesn’t happen. Food is MOST IMPORTANT (see below), so use the chance.The actual rim spaces are not good, this is were animals will appear, and they WILL appear. With 4 animals drawn each round (and many more through event cards) it is nearly certain that at some point they will appear in your rim village and trample your crop. On the other hand you want to be close to the animals, so you can hunt them. So I would suggest a space which is close to the rim, but not directly at the rim. If you play with the (recommended) fire rule, you might want to be close to the volcano as well (but not necessarily directly next to it). Being close to a river is a two-edged sword – your village should not be far away from river spaces, so you can send your people foraging, but being next to the river has a 33.3% chance that your village will be destroyed at some point in the game. But at some point a village of yours will be destroyed by SOMETHING anyway, it might as well be this one- after you milked it of it’s benefits.

If you take all these factors in account, there will be VERY FEW spaces that are interesting on the board. If you can, take one of them, most likely they will be taken already.

If you have to place a village close to another player, make sure that your direct neighbour is a good friend (this game has many “Diplomacy” elements). Be good to your neighbour, never attack him (only if it is necessary for YOUR victory, at the end of the game). You might even consider leaving him the one or other space you desire for harvest or hunting. But see below…..

2) “My best friend is my neighbour”

Oh yes, your neighbour is your best ally. Be soooo

good to him. He wants the space closer to the center of the board? Well, let him

have it! It simply means that your enemies will have to attack his units first

before they get to you! Your neighbour is your “wonder wall” who

protects your crop and your villages. You might lose a man or two to starvation

because you leave him the better spaces. Look vulnerable, just not too much. Wait

for the right moment. Attack your former friend when he is the most exposed.

Isn’t this game mean?

Oh yes, your neighbour is your best ally. Be soooo

good to him. He wants the space closer to the center of the board? Well, let him

have it! It simply means that your enemies will have to attack his units first

before they get to you! Your neighbour is your “wonder wall” who

protects your crop and your villages. You might lose a man or two to starvation

because you leave him the better spaces. Look vulnerable, just not too much. Wait

for the right moment. Attack your former friend when he is the most exposed.

Isn’t this game mean?

But seriously, the real reason for being friendly to your neighbour is that waging a war early on in the game can mean certain defeat. I have often seen grudge battles fought with masses of warriors (nyah, nyah, you abducted my lonely woman, nyah, nyah, so I know eradicate your village). Very often these battles will be fought against bad odds, thereby risking extinction of your tribe. You have so little units, so little resources, that any war which doesn’t possibly bring you INSTANT victory is silly. A skirmish here and there (see “food”) doesn’t hurt, but don’t overdo it. Be weaker than the leader, but stay much stronger than the weakest, and you will fare well for your “ end move” (again, see below)

3) The scourge of the event cards

“Das Tal der Mammuts” has horribly devastating event cards. There are so many ways to kill units, drown them, raze them by fire, bury them under stones, that there simply is no way to avoid them. You WILL suffer, one way or the other. But if your micromanagement of cards and manpower is ok, your chances of survival will rise.

Some basic things to ponder about:

- Keep those strong combat cards. The various booster cards for combat are the most valuable cards in the game. Keep them for the moments when the going gets tough - if you have one or two for the endgame, even better! Don’t waste them on skirmishes or grudge combats!

- USE the cards that devastate your enemies, they will do the same to you. But leave your CLOSE neighbour(s) alone!

- The “canoe” card that lets you cross rivers is better used as a defense against the flood, if you have an exposed village. Many other cards have defensive and offensive qualities, the defensive are the ones to look out for!

4) Gang up on the animals… or don’t…

Sometimes it looks wise to have as many warriors as possible attack that mammoth, while leaving the bear grazing next to it in peace.

If there is no other animal around, the gang tactic is of course good, but if you can reach more animals in one turn, it is actually wiser to distribute your attacks to raise your chances. The combat system is unforgiving, and even a big majority can lose a fight if the dice roll the wrong way. Why not try your luck?

Distributing is good – see it that way: If you lose one of these battles, you only lose one or two warriors – AND YOU HAVE TWO MOUTHS LESS TO FEED. You might even risk them on purpose - if they are successful they have “earned their meal”, and the whole tribe will profit, if not, these weak and feeble warriors will not endanger your food resources anymore. This truly is “survival of the fittest”!

5) Food – the overlooked problem

The game is most realistic in one point – winter is unforgiving and hard. Most players, especially in games with larger groups of people, underestimate the scarcity of food in winter. Having your people die of starvation is never elegant – these are wasted opportunities. They better had killed something before (or given birth, which is much, much more important than killing things – this is a moral game after all!).

It is possible to calculate roughly how much food you will probably get, so you can pretty much calculate how many of your tribe might die. If you begin the winter with only 4 food you’re in for many, many deaths. Better have them attack a strategic hex before they die anyway, don’t you think? You might even launch a stupid attack that will most probably fail miserably on purpose. It makes you look weaker for the moment, and you get rid of these hungry mouths. And if you DO suceed – even better! Just don’t overdo it – you want to have a considerable portion of your tribe survive for the next summer round. The earlier you send your warriors on suicide missions the better, they save more lives if they die early in the season, as strange as that sounds.

6) The end move

This game never lasts too long – I guess an average playing time is two years (game time, not REAL time, in case the casual reader wonders). When players have 2 villages and enough people the end move can happen any turn, and will happen. The player who is strong but vulnerable WILL be attacked at this point, and might have to forfeit a victory after such an attack. As in many games that mix “economics” and war, neither being the most aggressive attacker nor being the most busy defender will be good for winning the game.

Set up your final move carefully – Try to be behind in villages so you don’t have to move first and then suffer the consequences with all sorts of nasty cards and moves played against you. If possible an ideal end move could look like this: You have 2 villages that are well defended, because they are in reach of other players. Sneakily you move two “couples” (perhaps a “gay” couple among them, even sneakier!) in far away places in which nobody would usually build villages, like volcano spaces or rim spaces. It is important that other players can NOT reach these spaces in one move. They might be on to you immediately, but now all they can do is attack your well defended cities (for which you have hoarded combat cards, hehe) in the next round, if you survive, you’ll win!. If they get TWO moves against you, the far away villages will not have much hope, but if you moved last or second to last in the round BEFORE the final round this won’t happen. If your neighbour still loves you, s/he might actually be in the way of the attackers as well, but this is rare, because then s/he can also attack YOU!

| View/add comments here |

And don’t ask me about the best strategy to get “the fire” if you’re not close to the volcano – there isn’t one!

Have fun!

Moritz Eggert, 26.4.2003