Once again Moritz unwrapped a new

acquisition, and with his own special talent he began to translate the rules of the

game from English into understandable German off the cuff. Unfortunately he did not

know the answers to the usual detailed WPG questions about the rules and had himself

to struggle through the description. After 20 minutes we had all made our way

through the four printed pages of rules and had a vague notion of what was in store

for us.

Once again Moritz unwrapped a new

acquisition, and with his own special talent he began to translate the rules of the

game from English into understandable German off the cuff. Unfortunately he did not

know the answers to the usual detailed WPG questions about the rules and had himself

to struggle through the description. After 20 minutes we had all made our way

through the four printed pages of rules and had a vague notion of what was in store

for us.

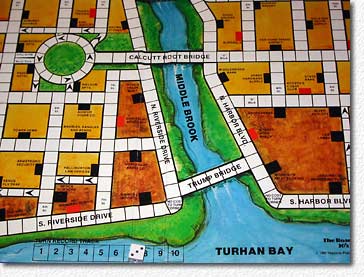

The game is set in an American city - the decade is of no great consequence - where crime syndicates are in full control. All the players are crime bosses; each one must transport his loot, expressed as a sum of money, from the scene of the crime to his own hideout. Each player draws a card at random, which gives the site of his hideout: this is his destination. Each one draws three more cards, which give the possible locations for his crime. He can choose which one of these is the starting point for his assignment. He should of course choose the one most convenient for his destination.

Each player has a car to transport the haul: he can drive this across the map of the city in full view of all the others, with a maximum of ten squares per move.

Each player in turn takes over the role of Police Chief and is thus in charge of a fleet of ten police cars with which he should prevent the mobsters from bringing home their loot. Each police car can move up to eight squares in one turn. The mobsters thus have a small advantage regarding how far their vehicles can travel, whereas the police clearly have the weight of numbers on their side.

Admittedly one police car alone does not pose

a problem to a criminal: he can drive past it without any restrictions. It takes two

police cars, piled up together on one single square, to create a barrier which can

not be passed. To put a mobster completely out of action requires as many as four

police cars which have to be moved to the area immediately surrounding their target.

The law enforcers thus have a very hard time in putting all the criminals out of

action. In short, three quarters of the mobsters will on average be able to bring

home the loot without problems.

Admittedly one police car alone does not pose

a problem to a criminal: he can drive past it without any restrictions. It takes two

police cars, piled up together on one single square, to create a barrier which can

not be passed. To put a mobster completely out of action requires as many as four

police cars which have to be moved to the area immediately surrounding their target.

The law enforcers thus have a very hard time in putting all the criminals out of

action. In short, three quarters of the mobsters will on average be able to bring

home the loot without problems.

But which ones are going to get caught? That depends on the one hand on the starting positions, which are scattered across the area of the city more or less at random, but on the other hand also on the personal relationships with the police, who are not above taking bribes. Before each round, each crime boss can donate an amount with which he can obtain the goodwill of the police force. This provides the Police Chief with some consolation for the fact that he will not be making a profit from crime in this round - live and let live. This bribery does not however provide a guarantee of freedom from punishment.

So far, so good: it sounds like a reasonable game, worth a rating above average.

But we now come to the decisive point.

The journey, which each mobster must drive from the location of the crime to his hideout, is completely random, in terms both of length and of the circumstances in the city. Someone who has drawn the right cards needs only to move along three squares and has reached home on his first move. Someone who is less fortunate must drive right across the city and has quite possibly no chance against ten police cars. The reward earned for success, that is, the value of the spoils, is also random. With good luck an untroubled 3-square journey can bring in 25,000 dollars; but with bad luck a player must struggle against the entire police force of the city for the sake of a sum only one tenth as big. What was the author thinking of when he dreamed up this principle?

In order to cover up to some extent the lack of logic in these developments, each player also has two event cards, with which he can influence the result of the plundering. For example, you can get out of jail for free, should you have been caught by the police. This is worth at least 1000 dollars, but only if you have landed in jail. Or you can clear a police car out of your way. This is worth something, should the police be hot on your heels, but the card is worthless for the majority of successful criminals. However, with the aid of a super-card at the end of the round you can carry off from an opponent his complete booty which he has just brought home safely. This can be worth as much as 25,000 dollars. This means the rival who has been taken by surprise also loses 25,000 dollars, making a net difference of 50,000 dollars. This is around ten percent of the total amount of money in circulation, or the entire proceeds from seven rounds of average criminal activity!

Does it make sense to be able to take a hard-earned prize away form a competing crime boss - a haul which perhaps he has successfully brought home by means of clever deceptive tactics - just because one happens to hold the right event card? And also because the opponent has not happened to draw a card with which he can ward off this hijack? Isn't this completely frustrating for one of the two of them? Does the author of the game really think that unpredictable chaos can on its own generate a good basis for a game?

These are questions of principle: what are the reasons for playing and what expectations does each player have when he sits down for an evening of games? I have my own decided point of view on this, which goes as follows:

If I am playing a game of intelligence, then, should I act more intelligently than the others, I want to see an advantage. In a memory game I want to be able to make capital out of my powers of memory, in a game of negotiations out of my diplomatic skills, in a game of pure luck out of the favour of fortune, and in a game of combat out of my experience in battle, my lion-hearted bravery or my aptitude for tactical lamentation. Whenever I decide to play a game, I want before I start to be able to assess which of my qualities as a player are going to be in demand.

What does "The Roaring 20's" have to offer in this respect? Unfairness in the difficulty of the task to be accomplished, a lack of logic in the respective prizes to be won, randomness in the fight against crime on behalf of the authorities, unpredictability in the asynchronous way one's competitors can have an effect. What does the game teach us? That the world is malicious and corrupt, that crime usually does pay, that neither planning nor skill are rewarded, and that the police are always on the side of those who have the most dollars.

As we now happen to be discussing this subject in the forum of the WPG: this game is "politically incorrect" in the extreme - this is also apparent in the accompanying description of the various assignments to be undertaken, in the way the author without any scruples suggests all kinds of crimes of burglary and theft, and cynically encourages bumping off security guards or stringing up one's rivals.

| View/add comments here |

The rating awarded by the Westpark-Gamers was a mediocre 2.5.

Walter Sorger, 25.4.2003 (translated by Mike Eggleton)

Some tips for winning strategies

Some tips for winning strategies

Of course “Tal der Mammuts” is not a clear-cut strategy game. Luck plays a huge factor in being successful in building a huge and prosperous tribe. Many an event card can ruin your best laid plans. But because there are some wargame elements in this game (very light ones, by the way), some tested strategies which work in games of this kind will better your chances in surviving the stone-age battle. And if you are already dependent on luck, why not better your chances by playing well?

1) Choosing your starting space

This might well decide if you win or lose, so it is a decision you should not make lightly. Many factors have to be taken into account. Of course it is preferable to be as far away of other players as possible (but see “my best friend is my neighbour” below), so spaces close to the rim of the board are more interesting than central ones, where everybody will be your enemy. You should always choose a plain hex as a starting space, chances are good it will see a crop if you use the initial planting rule. Later in the game it will be much more difficult to see your crop grow, actually I’ve yet to see a game with many high-yielding crops, it just doesn’t happen. Food is MOST IMPORTANT (see below), so use the chance.The actual rim spaces are not good, this is were animals will appear, and they WILL appear. With 4 animals drawn each round (and many more through event cards) it is nearly certain that at some point they will appear in your rim village and trample your crop. On the other hand you want to be close to the animals, so you can hunt them. So I would suggest a space which is close to the rim, but not directly at the rim. If you play with the (recommended) fire rule, you might want to be close to the volcano as well (but not necessarily directly next to it). Being close to a river is a two-edged sword – your village should not be far away from river spaces, so you can send your people foraging, but being next to the river has a 33.3% chance that your village will be destroyed at some point in the game. But at some point a village of yours will be destroyed by SOMETHING anyway, it might as well be this one- after you milked it of it’s benefits.

If you take all these factors in account, there will be VERY FEW spaces that are interesting on the board. If you can, take one of them, most likely they will be taken already.

If you have to place a village close to another player, make sure that your direct neighbour is a good friend (this game has many “Diplomacy” elements). Be good to your neighbour, never attack him (only if it is necessary for YOUR victory, at the end of the game). You might even consider leaving him the one or other space you desire for harvest or hunting. But see below…..

2) “My best friend is my neighbour”

Oh yes, your neighbour is your best ally. Be soooo

good to him. He wants the space closer to the center of the board? Well, let him

have it! It simply means that your enemies will have to attack his units first

before they get to you! Your neighbour is your “wonder wall” who

protects your crop and your villages. You might lose a man or two to starvation

because you leave him the better spaces. Look vulnerable, just not too much. Wait

for the right moment. Attack your former friend when he is the most exposed.

Isn’t this game mean?

Oh yes, your neighbour is your best ally. Be soooo

good to him. He wants the space closer to the center of the board? Well, let him

have it! It simply means that your enemies will have to attack his units first

before they get to you! Your neighbour is your “wonder wall” who

protects your crop and your villages. You might lose a man or two to starvation

because you leave him the better spaces. Look vulnerable, just not too much. Wait

for the right moment. Attack your former friend when he is the most exposed.

Isn’t this game mean?

But seriously, the real reason for being friendly to your neighbour is that waging a war early on in the game can mean certain defeat. I have often seen grudge battles fought with masses of warriors (nyah, nyah, you abducted my lonely woman, nyah, nyah, so I know eradicate your village). Very often these battles will be fought against bad odds, thereby risking extinction of your tribe. You have so little units, so little resources, that any war which doesn’t possibly bring you INSTANT victory is silly. A skirmish here and there (see “food”) doesn’t hurt, but don’t overdo it. Be weaker than the leader, but stay much stronger than the weakest, and you will fare well for your “ end move” (again, see below)

3) The scourge of the event cards

“Das Tal der Mammuts” has horribly devastating event cards. There are so many ways to kill units, drown them, raze them by fire, bury them under stones, that there simply is no way to avoid them. You WILL suffer, one way or the other. But if your micromanagement of cards and manpower is ok, your chances of survival will rise.

Some basic things to ponder about:

- Keep those strong combat cards. The various booster cards for combat are the most valuable cards in the game. Keep them for the moments when the going gets tough - if you have one or two for the endgame, even better! Don’t waste them on skirmishes or grudge combats!

- USE the cards that devastate your enemies, they will do the same to you. But leave your CLOSE neighbour(s) alone!

- The “canoe” card that lets you cross rivers is better used as a defense against the flood, if you have an exposed village. Many other cards have defensive and offensive qualities, the defensive are the ones to look out for!

4) Gang up on the animals… or don’t…

Sometimes it looks wise to have as many warriors as possible attack that mammoth, while leaving the bear grazing next to it in peace.

If there is no other animal around, the gang tactic is of course good, but if you can reach more animals in one turn, it is actually wiser to distribute your attacks to raise your chances. The combat system is unforgiving, and even a big majority can lose a fight if the dice roll the wrong way. Why not try your luck?

Distributing is good – see it that way: If you lose one of these battles, you only lose one or two warriors – AND YOU HAVE TWO MOUTHS LESS TO FEED. You might even risk them on purpose - if they are successful they have “earned their meal”, and the whole tribe will profit, if not, these weak and feeble warriors will not endanger your food resources anymore. This truly is “survival of the fittest”!

5) Food – the overlooked problem

The game is most realistic in one point – winter is unforgiving and hard. Most players, especially in games with larger groups of people, underestimate the scarcity of food in winter. Having your people die of starvation is never elegant – these are wasted opportunities. They better had killed something before (or given birth, which is much, much more important than killing things – this is a moral game after all!).

It is possible to calculate roughly how much food you will probably get, so you can pretty much calculate how many of your tribe might die. If you begin the winter with only 4 food you’re in for many, many deaths. Better have them attack a strategic hex before they die anyway, don’t you think? You might even launch a stupid attack that will most probably fail miserably on purpose. It makes you look weaker for the moment, and you get rid of these hungry mouths. And if you DO suceed – even better! Just don’t overdo it – you want to have a considerable portion of your tribe survive for the next summer round. The earlier you send your warriors on suicide missions the better, they save more lives if they die early in the season, as strange as that sounds.

6) The end move

This game never lasts too long – I guess an average playing time is two years (game time, not REAL time, in case the casual reader wonders). When players have 2 villages and enough people the end move can happen any turn, and will happen. The player who is strong but vulnerable WILL be attacked at this point, and might have to forfeit a victory after such an attack. As in many games that mix “economics” and war, neither being the most aggressive attacker nor being the most busy defender will be good for winning the game.

Set up your final move carefully – Try to be behind in villages so you don’t have to move first and then suffer the consequences with all sorts of nasty cards and moves played against you. If possible an ideal end move could look like this: You have 2 villages that are well defended, because they are in reach of other players. Sneakily you move two “couples” (perhaps a “gay” couple among them, even sneakier!) in far away places in which nobody would usually build villages, like volcano spaces or rim spaces. It is important that other players can NOT reach these spaces in one move. They might be on to you immediately, but now all they can do is attack your well defended cities (for which you have hoarded combat cards, hehe) in the next round, if you survive, you’ll win!. If they get TWO moves against you, the far away villages will not have much hope, but if you moved last or second to last in the round BEFORE the final round this won’t happen. If your neighbour still loves you, s/he might actually be in the way of the attackers as well, but this is rare, because then s/he can also attack YOU!

| View/add comments here |

And don’t ask me about the best strategy to get “the fire” if you’re not close to the volcano – there isn’t one!

Have fun!

Moritz Eggert, 26.4.2003